Adam Sanregret had just graduated from college when he bought his first home, which he describes as “a 1910 beater.”

By day, he was a high school band director. At night, he studied subjects like plumbing and electrical wiring. He restored the house himself, sold it, and turned his experience into a career in real estate. Since 2003, he’s been bringing together buyers and sellers of historic and older homes in need of restoration, and has earned recognition from the local preservation society.

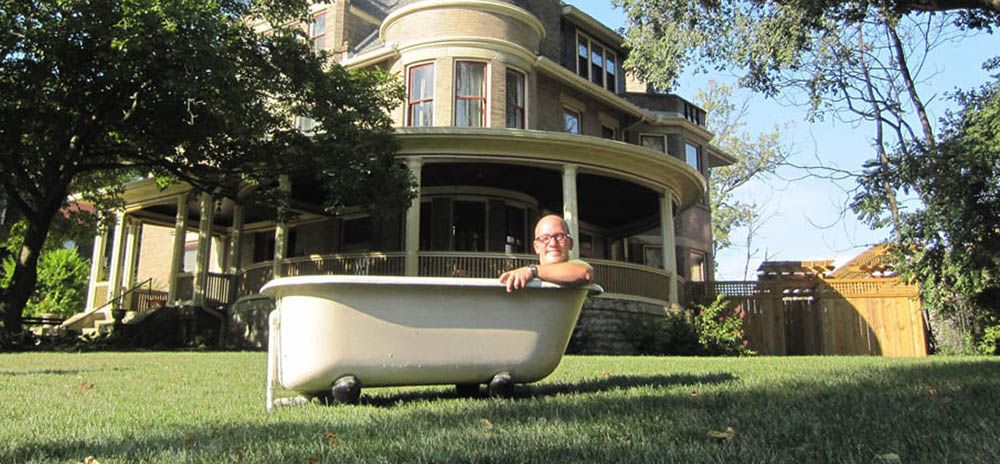

Here, Sanregret goes in-depth about his fifth and most recent project, an 1896 Queen Anne-style Victorian home in Cinncinnati’s historic Rose Hill neighborhood.

As I walked into this house the first time, the last thing on my mind was buying it. I was trying to sell it. My clients were looking for a historic home that could use some TLC, and I thought this one might work for them. But the house begged for way more attention than they were prepared to give.

What struck me wasn’t the work it needed, but the historical detail. The original lighting, fixtures and woodwork were mostly intact. The wall switches and doorknobs were the originals. You don’t come across a time capsule like this every day.

I bought it for $237,000 and planned to spend another $100,000 on restoration, doing most of the work myself. This was the most ambitious project I had ever attempted. For the next 11 years, it would be my home and second occupation.

A Bad Roof Can Ruin Everything

Based on my experience with other restorations, I knew the cardinal rule: fix the roof first. There’s no point starting anywhere else when your work could be ruined by the next rainfall. I had the roof inspected and, to my amazement, it needed nothing. It was structurally solid, if not perfect in every way.

The Plumbers Wanted Too Much

My second priority: plumbing. If there’s one thing a home needs to be habitable, it’s functional plumbing.

When I flushed a toilet, water would stream down the walls below. The two full bathrooms on the second floor had the original marble sinks and porcelain bathtubs and toilets. Fixtures like that can last forever, but every inch of brass pipe had eroded, become brittle and had to be replaced.

I got bids from several contractors, and all came in around $25,000 — a lot higher than I expected. It made more sense to do the work myself. I figured it would take 30 to 40 hours, plus the cost of materials. I spent $1,000 on supply pipes (the ones behind walls) made of CPVC plastic. For the visible sections, I stayed true to history and used threaded brass with chrome fittings at a cost of $2,500.

When I flushed a toilet, water would stream down the walls below. The two full bathrooms on the second floor had the original marble sinks and porcelain bathtubs and toilets. Fixtures like that can last forever, but every inch of brass pipe had eroded, become brittle and had to be replaced.

I got bids from several contractors, and all came in around $25,000 — a lot higher than I expected. It made more sense to do the work myself. I figured it would take 30 to 40 hours, plus the cost of materials. I spent $1,000 on supply pipes (the ones behind walls) made of CPVC plastic. For the visible sections, I stayed true to history and used threaded brass with chrome fittings at a cost of $2,500.

Doing this myself required time and improvising. I showered at the gym for a month.

Updating Old Electrical? It’s Not a DIY Job

I had better luck hiring a professional to install an up-to-code electrical service panel with circuit breakers. Total cost: $1,750. This is a job for a licensed electrician, not something I advise tackling on your own.

I did know enough to rewire the rooms and light fixtures. I ended up replacing about 85 percent of the original knob-and-tube wiring and installing 40 additional outlets. The bottom line was $3,000. The old wiring that remained in place is fully up to code.

After that first month, I had working bathrooms and could plug in the microwave without fear. I camped out for the next year on the third floor — intended for servants — with a dorm-size refrigerator and paper plates. It’s hard to keep a girlfriend during renovations.

You Can’t Learn Plastering From a Book

Plaster was widely used to finish interior walls until the mid-20th century. Plastering is an artform. You can wire or plumb a house by following codes and procedures, but getting a smooth, uniform plaster finish takes talent. You either have the gift or you don’t.

I don’t, so I hired a pro. I knew plaster was missing in places — there was plywood on a bedroom ceiling to keep raccoon droppings out. But it wasn’t until the plasterer handed me his $23,000 estimate that I realized just how bad things were. About a third of the plaster in the house was in a state of decay and had to be redone.

The rooms are large — the foyer is 18 feet wide — so the plasterer basically lived with me for the next few months. The final bill matched the estimate, but it was still double my original guess.

I don’t, so I hired a pro. I knew plaster was missing in places — there was plywood on a bedroom ceiling to keep raccoon droppings out. But it wasn’t until the plasterer handed me his $23,000 estimate that I realized just how bad things were. About a third of the plaster in the house was in a state of decay and had to be redone.

The rooms are large — the foyer is 18 feet wide — so the plasterer basically lived with me for the next few months. The final bill matched the estimate, but it was still double my original guess.

Old Homes Don’t Know About Efficiency

With the major jobs — plumbing, electric and plastering — out of the way, I could move on to plugging a gaping hole in my pocket. During the first winter, my monthly utility bill hovered around $1,800. Taking care of the energy drain set up my next round of priority projects.

First up was getting the windows in shape. Some of them didn’t shut properly, which I could fix. A previous owner had installed aluminum storm windows, but many had cracked glass (or none at all) and frame damage. An average-size storm window costs about $200 at a big box store. I saved a little by having a local hardware company do repairs.

I needed a particularly large storm window for the foyer, where a stained-glass window depicts the Greek goddess Persephone — all 8 feet by 8 feet of her. Stained glass is beautiful, but it’s like making a window out of Swiss cheese, with hundreds of tiny holes that welcome in the cold. There had never been a storm window protecting Perspephone, and I can understand why. I had to have one custom made to the tune of $1,500.

Next, I headed to the attic to give the house its first insulation, and to the basement, where the original, inefficient “gravity” furnace was still chugging away. In came two high-efficiency gas furnaces, plus a central air conditioner — $8,000 for the trio. I didn’t have to worry about removing the old thermostat because there wasn’t one.

I also modified the ductwork to let me heat/cool only select rooms, usually the living room, kitchen and master bedroom.

Once the efficiency work was done, my winter utility bills averaged $700, a monthly savings of $1,100.

Porches and Chimneys Don’t Care About Your Plans

After taking care of the critical work, my plan was to take on one major project a year for the next 10 years, doing the work myself and spending $3,000 to $4,000 in materials on each. I wanted to finish the master bedroom, so I would have a place to sleep besides the servants’ digs.

My plans were dashed when, after more than a century on the job, the roof over the wraparound porch collapsed before my eyes, taking a curved gutter with it. I knew the porch’s wood decking, or ceiling, was soft, but I thought it would hold up until I finished the work inside. I had to quit what I was doing and erect a new roof with help from a roofer friend. The materials set me back $5,000, fancy gutter included.

Not long after that, the top section of the chimney gave up the ghost. I figured I could repair it myself for $4,000 or less. But by the time I was done, I had spent $12,000.

After these detours, I finished the rooms in order of importance — master bedroom, kitchen, and so on.

Not every project had to do with historic preservation. I converted the three servants’ rooms on the third floor into a guest suite — bedroom, kitchenette, bathroom — with modern materials like granite counters and subway tile. I rented it to travelers.

I decided that an outdoor entertaining space would be nice, so I built a pergola patio. I dropped $8,000 on that one because I splurged on a hot tub.

Curated Hoarding? Custom Milling? This Is the Fun Part No One Tells You About

Part of the charm of a historic home is the abundance and variety of wood found inside. Mine has wood trim, baseboards, and door and window casings and each of the four rooms on the first floor has a different species of wood, from bird’s eye maple to rosewood. Much of it was intact, but plenty was rotted, damaged or missing altogether.

You can buy replacement wood easy enough. But the grain you see is the result of the milling technique used by the original artisan. Finding enough of the correct species of wood — milled in the exact same way — requires a supernatural coincidence.

“Owning an old house is like being a curator.”

Here’s my workaround: I took samples of each type of original wood to a lumber mill, which created a milling template from them, and then milled new wood for me using the template. The results were indistinguishable from the wood milled in 1896. If that sounds expensive, I have good news. The mill charged me $250 for making the template, and $1 per linear foot for the wood.

The pieces of wood that I replaced are still in the house, stashed in the basement along with other scraps of original material. Owning an old house is like being a curator. I never throw anything away, whether it’s a hinge, baseboard or square of tile. The house is going to be here long after I’m gone. You never know what purpose these artifacts might serve in the future.

“Owning an old house is like being a curator.”

Here’s my workaround: I took samples of each type of original wood to a lumber mill, which created a milling template from them, and then milled new wood for me using the template. The results were indistinguishable from the wood milled in 1896. If that sounds expensive, I have good news. The mill charged me $250 for making the template, and $1 per linear foot for the wood.

The pieces of wood that I replaced are still in the house, stashed in the basement along with other scraps of original material. Owning an old house is like being a curator. I never throw anything away, whether it’s a hinge, baseboard or square of tile. The house is going to be here long after I’m gone. You never know what purpose these artifacts might serve in the future.

“Once you take something out, you can’t put it back.”

My house could never be built today the way it was in 1896. Building codes change. Most out-of-code features are often grandfathered in, meaning you can keep them in place — but once you take something out, you typically can’t put it back.

Old staircases, for example, tend to be steeper than would be allowed today. You can restore that old staircase where it sits, but you can’t tear it down and rebuild it the same way. The same rule applied to the house’s 10-gallon flush toilets, which remain in their original spots.

Is it historic?

The National Register of Historic Places criteria for historic home registration lists a strict set of guidelines. Restorers and real estate agents might use the term historic for a home built before 1935, or one with historical or architectural significance (such as a mid-century modern structure).

“I had no guilt about ripping stuff out.”

Some things deserve to be removed, grandfathered in or not. I kept what remained of the original kitchen — wood moldings, a built-in butler’s pantry and a wall-mounted enunciator box that summoned staff. Everything else was from a 1950s-era redo (think: rusty metal cabinets), and I had no guilt about ripping that stuff out.

Dubious updates like this are known as remuddling, and thankfully it was limited to the kitchen. Some remuddling can be undone, but often the original fixtures and materials are long gone.

“Their expertise was free, and they were glad to help.”

Even though I did most of the work myself, I didn’t really go it alone. I belong to a local organization of old-house enthusiasts, including skilled professionals like architects and engineers. I sketched out my plans, and they helped me with advice, corrections and enthusiasm. With any DIY restoration, it helps to get connected to local experts.

“Restoring a house is … like rescuing a stray dog.”

Restoring a house is an emotional experience, like rescuing a stray dog. Most buyers do it because they’re passionate about it, not to make a profit. Still, I would limit the total investment to the home’s after-restoration value unless you’re willing to take the financial risk of losing more.

There are buyers who can well afford to do whatever they want — and more power to them. I had clients who put $400,000 into an 1840s Greek Revival in a neighborhood where the highest sale price ever was $125,000. They won’t come out ahead unless they stay put for the next 30 years. But they fulfilled a lifelong dream, and it’s hard to quibble with that.

There are buyers who can well afford to do whatever they want — and more power to them. I had clients who put $400,000 into an 1840s Greek Revival in a neighborhood where the highest sale price ever was $125,000. They won’t come out ahead unless they stay put for the next 30 years. But they fulfilled a lifelong dream, and it’s hard to quibble with that.

As for me, my $100,000 restoration budget turned out to be naïve. I exceeded it by $50,000, or 50 percent. The plaster was in far worse shape than I thought. I didn’t realize how much a chimney repair could cost. And, I suppose the fancy patio didn’t help matters.

But I still came out okay. Home values have increased dramatically in the past few years. The house was saved — and I sold it earlier this year, 11 years after I started, for a gratifying profit.

“You don’t have to do it like I did it.”

It’s important to know you don’t have to do it like I did it. I went the DIY route, which demands skill and time. My clients who’ve hired contractors to do all the work have restored their homes in as little as three months.

And because I sold my house prior to this one quicker than I expected, I had no time to make living arrangements and had to move into the house, as it was. Normally, I would’ve lived somewhere else for the first few months. I don’t recommend showering at the gym every day if you can help it.

If you’re thinking of buying, consider getting an agent who deals in historic homes and can guide you through this process. You might also look into the government-insured mortgage known as an FHA 203(k) loan. Many of my clients finance their restorations this way. These loans may cover the purchase of the house and the estimated cost of renovations — with renovation funds held by the title company and dispersed to contractors as work is completed.

With the right guidance, planning and funding, it doesn’t need to take 11 years to complete a restoration.

Get a quote

Includes personal service from a Farmers agent.

Written by

The information contained in this page is provided for general informational purposes only. The information is provided by Farmers® and while we endeavor to keep the information up to date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to this article or the information, products, services or related graphics, if any, contained in this article for any purpose. The information is not meant as professional or expert advice, and any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

Related articles