"My family and I were living in northern Cincinnati when a tornado touched down just a few blocks from our house. "

— Mark Elliott

On a muggy May evening in 2003, Pete Abilla and his wife were driving home from a date night when they saw something cross the freeway about a mile ahead of their minivan.

The road — I-35 outside of Edmond, Oklahoma — was slick from a thunderstorm. “It looked like a sandstorm,” recalls Abilla. In fact, it was a category E F-3 tornado. Abilla uses just two words to describe it: “huge” and “scary.”

As the couple approached the area the storm had just passed through, they saw catastrophic destruction. A bus laying on its side, a church totally destroyed. Abilla looked for survivors while his wife comforted a woman with a deep gash in her back. Minutes later a helicopter evacuated the injured and the Abillas left for their own safety.

Unlike other severe weather, which can be forecast days in advance, tornadoes develop quickly, allowing only moments to flee or find shelter. Still, there are ways to prepare.

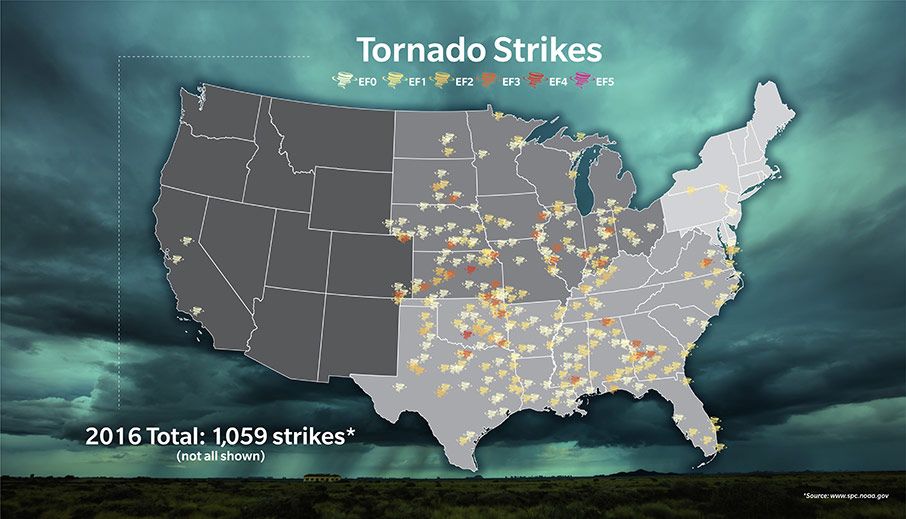

Tornadoes can strike anywhere.

Tornado Alley, a swath of land from Texas to Nebraska, is most prone to destructive vortexes, but tornadoes can strike anywhere. Random tornadoes have formed in areas far outside of Tornado Alley in recent years, touching down in cities from outside Sacramento, California, to Long Island, New York.

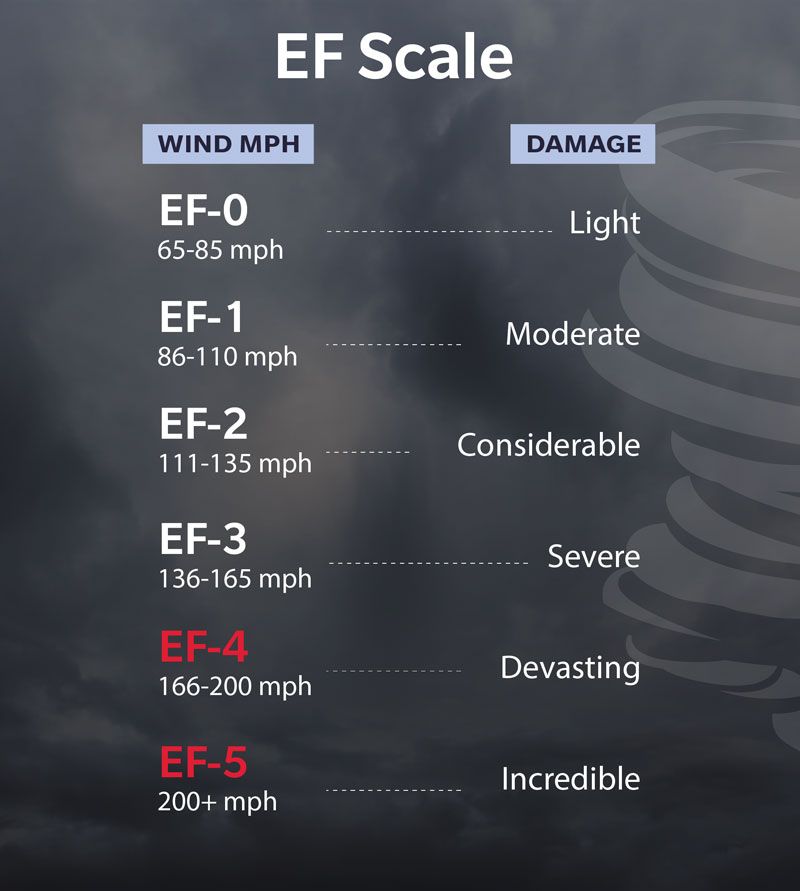

Tornadoes — which are capable of producing 300 mph winds and stretching one-mile wide — rank among nature’s fiercest storms. “When you see a tornado, first you’re in awe,” says Danielle Dozier, a Certified Broadcast Meteorologist at FOX 59 in Indianapolis. “Then you’re devastated because you’re literally seeing homes fly in the air and people getting hurt.” As a meteorologist and storm chaser in Oklahoma City, Dozier witnessed the 2013 E F-5 tornado that destroyed Moore, Oklahoma and killed 24 people.

Enhanced Fujita (EF) Tornado Damage Scale

The Fujita Tornado Damage Scale, originally developed in 1971 by Theodore Fujita at the University of Chicago, was updated to the Enhanced F (EF) Scale in 2007 by a panel of meteorologists and engineers at Texas Tech University’s Wind Science and Engineering Research Center. The scale outlines wind speed ranges and damage categories, which also include detailed descriptions for examples of damage to 23 types of buildings and additional objects, such as trees and towers.

There is no “tornado season.”

Although most tornadoes occur from April to June, a rare January tornado recently killed 18 people in Georgia and Mississippi. In fact, powerful tornadoes can occur any day of the year if warm, moist air near the ground meets dry, relatively cool air above that by way of a “lift” (think: fronts or an outflow from an old storm), according to Harold Brooks, Senior Research Scientist at National Oceanic and Atmospherics’ (NOAA) Severe Storms Laboratory in Norman, Oklahoma. In addition, the frequency of tornado outbreaks — six or more tornadoes occurring in close succession — has noticeably increased since 1965, although scientists don’t know why.

"Flying debris is the number one cause of death in tornadoes."

— Meteorologist Danielle Dozier

Wes Micholosky’s client was the first to notice the perfect sunlit sky, surrounded by dark clouds, as the two were leaving a business meeting in Windsor, Colorado. What quickly followed was the first sign of an E F-3 tornado that hit on May 22, 2008. “Right then hail and wind started coming en masse,” says Micholosky.

"The sky was just gross. [My client] yelled, ‘We’re in the eye!’"

— Wes Micholosky

Not only are tornadoes difficult to forecast, the average lead-time from tornado warning to impact is around 15 minutes, according to Dozier. Recognizing the warning signs of a tornado — some people report seeing a pale green sky — could add precious time for you to find shelter. The weather expert community has a few unproven theories about why people perceive a greenish atmosphere before a tornado, according to Dozier. One theory: the way sunlight scatters behind the storm cloud at sunrise or sunset produces the noteworthy hue. Other warning signs listed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) include large hail, dark, low-lying clouds and a loud roar, like a freight train.

Common places to find safe shelter

At home: The basement, if your home or building has one. The innermost rooms with the fewest windows, such as a hall closest or bathroom, are also safe places to shelter inside a home. Bathrooms can offer additional protection because pipes reinforce the walls and lying in the bathtub provides an extra barrier from flying debris.

Away from home: A concrete, single-story structure may be your safest bet. Dozier advises against sheltering inside big box stores, which may have roofs that can get ripped off in high winds. Tornado survivor Micholosky also recommends avoiding storefronts. “Most [storefronts] have relatively cheaper awnings and signage,” he says. “All of those big letters are the first things to be thrown at 100-plus miles per hour.”

"As we ran inside, the wind got so intense the windows of the bank shattered."

— Wes Micholosky

In your car: One recommendation N O A A suggests: drive toward shelter if no sturdy shelter is in sight and the tornado is in the far distance. If you can determine the tornado’s path, drive at a right angle — i.e., perpendicular to the storm, says Dozier. Though most tornadoes move from southwest to northeast, they can double back so keep an eye on the skies. When a twister is close, you may decide to pull over to a low-lying area but avoid underpasses, which can amplify wind speeds and turn into wind tunnels, according to Dozier. Once parked, the N O A A recommends getting as far away from your car as possible. While your car may feel like it offers protection, violent tornadoes can hurl cars hundreds of yards.

"All of my windows and mirrors were ripped from the vehicle."

— Wes Micholosky

If you’re running away from your car or you’re caught outside, look for an open field and lay face down in a spot lower than ground level. If you can’t find a ditch, crouch by a strong building. Cover your head with clothing, a purse or a backpack and your hands, but don’t clasp your hands together. Micholosky recommends laying one hand over the other. “If one hand takes a tangerine-sized hail shot, your other hand is still functioning and uninjured,” says Micholosky. “Trust me, you’ll need all the body parts you can use.”

Weather radios and apps can be lifesavers at night.

"The siren noise from a monitor would have woken us up and allowed us to get out sooner."

— Robert Sollars

Tornadoes that strike late at night or before the sun rises can contribute to the loss of life because people are caught off-guard. Robert Sollars, his wife and child were asleep in their Missouri home when a tornado passed. The family survived, but it was a too-close call for Sollars’ comfort. He immediately went out and bought a weather warning monitor. To receive an instant heads-up when a tornado warning is issued, these monitors sound audio alarms triggered by major weather alerts.

- N O A A weather radio: Akin to a smoke detector for severe weather, these radios range in price from $30 to $100 and can be purchased online and other retail or hardware stores.

- N O A A Weather Alerts smartphone app: For $3.99, the app issues a loud, piercing siren for weather alerts within the distance you specify by enabling the app’s location services and push-notifications.

Research pre-fab shelters and safe rooms.

F E M A offers a guide to building an in-residence shelter. Many municipalities also offer funding to help pay for these shelters. Specific dollar amounts and requirements vary widely, but your local Storm Hazard Mitigation Officer can advise you on the types of grants available and how much you may be eligible for.

“At my house, it’s a walk-in closet off our bedroom with six-inch-thick reinforced concrete and a steel door with three locks.” — Harold Brooks, N O A A Senior Research Scientist

Brooks advises against building a DIY outdoor shelter. Tornadoes last an hour — tops — and constructing a freestanding shelter capable of withstanding 200 mph winds is extremely difficult. Brooks notes ready-made, eight-ton transportable monolithic concrete domes may be a viable solution for a home shelter. Some communities in Tornado Alley, such as Locust Grove, Oklahoma, have adopted this curved, concrete style of building for schools that double as community shelters.

Double-check your stock of safety and clean-up supplies.

"Don’t go cheap on garbage bags."

— Marie Porter

Marie Porter’s Minneapolis home was damaged in an E F-2 twister on May 22, 2011, while she was out running errands. Looking back, she says having a ready supply of heavy-duty contractor bags in your disaster preparation supplies may seem like a little thing. But it’s the little details that make a huge difference in the aftermath, when basics may be a rare but essential commodity for cleaning up heavy-duty, dangerous debris like nails, glass and splintered wood.

Other supplies to consider including:

- Bike helmets or construction hard hats to help protect against head trauma from flying debris.

- A loud police whistle to help rescuers locate you if you’re in a shelter or trapped under debris. Tornado veteran John Snow, Regents’ Professor Emeritus of Meteorology at the University of Oklahoma, notes the high-pitched sound of a whistle carries farther than a human voice.

- Disposable cameras to document damage for an insurance claim. Take photos of the damage before starting to clear debris, says Porter, who knows from personal experience that a home may be without electricity — and no way to charge your phone or other digital camera — for several days.

Written by

The information contained in this page is provided for general informational purposes only. The information is provided by Farmers® and while we endeavor to keep the information up to date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to this article or the information, products, services or related graphics, if any, contained in this article for any purpose. The information is not meant as professional or expert advice, and any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

Related articles